The Trust’s director of external affairs Jane Tully reflects on the Wyman Review of debt advice funding.

The Trust’s director of external affairs Jane Tully reflects on the Wyman Review of debt advice funding.

After an eventful 2017, it is already clear that 2018 will prove to be a truly pivotal year for the future of debt advice.

The Bill creating the new Single Financial Guidance Body (SFGB) is completing its passage through Parliament, the Treasury is forming its plans for breathing space and the Money Advice Service (MAS) are implementing their commissioning strategy.

Added to this, we now have the recommendations from Peter Wyman’s Independent Review of the Funding of Debt Advice to chew over. The review explores the Government’s support offer for people in financial difficulty, covering long-standing questions including ‘who’ should pay for advice and ‘how’ free-to client advice should be funded.

While not everyone might agree with its contents – and it goes far wider than just these two questions – it has certainly given us lots of food for thought. Here’s a quick round up, and some early thoughts…

The focus on efficiency is right…

Wyman will undoubtedly find wide agreement on the current imbalance of supply, demand and need for advice – something those of us close to service delivery are all too familiar with. Working with London Economics to review the macro and micro economic and advice trends, he concludes that overall the amount of free advice available needs to increase by 50% – to a further 1.65m people, over the next two years – and possibly by more, depending on external economic variables. To get there, he proposes more funding through the levy (an additional £10m a year for each of the next two years), alongside efficiencies through channel shift, reductions in duplication, improved use of technology and collaboration. So far, so good.

…but the ‘channel shift’ references are muddled…

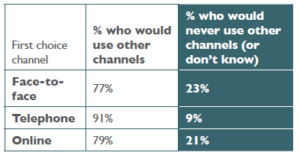

The review proposes that proportionately more people would be helped via ‘lower cost channels’ – phone (15% of face-to-face demand would be ‘shifted’ to phone) and online (20% of telephone demand would be ‘shifted’ to online). This is supported by evidence from MAS’s annual survey of the over-indebted population, which suggests that 77% of those whose first choice of channel is face-to-face would use another channel (and 91% for phone and 79% for online). Of course, this doesn’t necessarily mean that these delivery channels are right for these client’s debt circumstances – it simply gives an indication of the scope for change based on people’s own channel preferences.

I am in no doubt that we can help more people this way, although I would argue it would be through ‘multi-channel’ approaches rather than the more dated notion of simple ‘channel shift’ – for example, by encouraging more people to do an online budget in advance of a call or session, pre-populating income and expenditure (I&E) online, using digital for follow-up etc). At the same time, I am hugely conscious that as we see more and more vulnerable clients, and people with priority debts and deficit budgets, intensive case-work type support, either by phone or face-to-face will continue to be essential – and expensive).

The proposed (small) increase in funding for face-to-face advice will be welcome here – but given wider cuts to face-to-face advice, whether this increase is sufficient to satisfy the SFGB’s statutory duty to focus on those most in need and people who are vulnerable remains to be seen.

The actual targets are unhelpful

A key message coming from the report is that free-to-client providers should commit to a 20% efficiency saving. The principle and challenge of working smarter is quite right, but the devil will be in the application. Does this apply to all channels and models of advice? And surely some will be further ahead (or behind) on an efficiency journey – making those savings harder (or easier) to come by from their current starting point. Or is it something we commit to achieving collaboratively, and using technology (where I believe there are much greater opportunities)?

My main concern is the tendency for decision makers (and here I mean those further away from direct commissioning) to adopt single numbers and reductive messages like these, and apply them without regard to circumstances (such as channel/model of advice/pace of change/other demands such as quality/level of vulnerability).

While the overall ambitions around efficiency are right – my plea would be to approach this with care.

The right tech will be crucial

Technology is central to achieving greater efficiency particularly through investment in shared platforms. The review mentions three that hold promise:

- a platform that facilitates a single I&E, owned by the client which can be shared with advice agencies and creditors (and ideally could be pre-populated using credit referencing or open banking data)

- a mechanism to enable creditors to refer more easily to advice (possibly linked to open banking); and

- a shared platform to facilitate quality assurance (particularly crucial for smaller agencies).

Beyond that, and with a look to the future, investment in machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI) are also proposed. None of these are particularly new or radical, however what agencies would value on these is co-ordination, investment and – crucially – someone to take on the risk. What we definitely don’t need is challenge prizes or small innovation pots, which in this context are unlikely to deliver the changes needed. Perhaps this is an area where the new SFGB may act.

We’re still not much clearer on who should fund advice…

The whole point of this review has been to address the question of how advice should be funded. This has long been a point of debate, and has become increasingly pertinent as agencies see more clients with priority debts (increasingly relating to arrears on household bills as opposed to consumer credit) and deficit budgets, and with funding directly from the public sector continues to be cut.

Wyman concludes that the first port of call for funding should be those who make a profit from credit. While he makes the case that that the statutory government debt advice levy should be increased overall, he also argues that this should continue to be paid by financial services only. Given the change in debt profile in recent years, I imagine the banks will have a thing or two to say here…

Where Wyman does go further, however, is in relation to Fair Share, where he proposes tighter implementation and enforcement through voluntary codes of conduct setting clear expectations of paying Fair Share pro-rated to debts repaid, to be adopted by various sector trade bodies. The challenge here is that this relies on voluntary action on the part of the trade bodies, and still won’t capture the growing number of public sector debts.

The question over quality….

The question over quality of advice has risen up the agenda in recent months, and here Wyman proposes that all providers have quality assurance process authorised by the FCA, and that all authorised debt advisers have a debt-specific qualification, with key elements agreed by the FCA. There are interesting arguments on either side of this, especially given the context (for instance, the sheer number of small agencies, and reliance on volunteers). Whether the FCA would want to take this on, or leave it to the new SFGB to manage through their funded projects (an easier process perhaps, but one that would only apply to part of the sector), is another question.

…not enough on solutions…

The report talks about funding for DROs, yet there is no mention of bankruptcy – and in fact the report as a whole is light on distinguishing between funding from general advice and of specific solutions.

…and finally, the many tsars!

Under the Financial Guidance & Claims Bill, there are plans to devolve debt advice delivery funding to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland – with the SFGB continuing to have oversight of a UK-wide Debt Advice Strategy. To drive forward the recommendations in his review, Wyman proposes that government appoint a ‘Debt Advice Tsar’ – in fact, not just one, but four! The mind boggles as to how this would work in our already complicated landscape….

So where does this go next?

The recommendations in the report are just that – recommendations – and any decision to adopt them will sit with the respective bodies and groups listed in the report. I suspect this review won’t quite put to bed many of the long-standing debates in our sector, but it does at least give us something to rally around.

You can read the Wyman review here.